This is a re-posting of an article published on The Conversation

When street artist Jason “Revok” Williams sprayed his trademark chevrons on a handball court in Brooklyn, he probably didn’t imagine he would end up in a legal fight with a high-street fashion giant for breach of copyright.

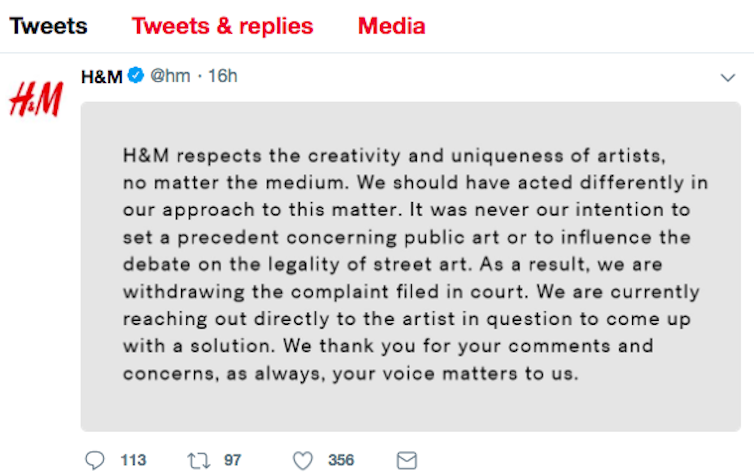

But in January 2018, that’s what happened – and Swedish retailer H&M retaliated with a lawsuit, rejecting Williams’ claims and dubbing his work “vandalism”. Then came a series of intriguing twists. On March 15, H&M issued a tweet about “withdrawing the suit”, following a backlash against the retailer. Williams’ lawyer then confirmed that, despite earlier statements, H&M was not dropping the lawsuit. The ongoing furore raises an interesting issue: can illegal graffiti be protected by copyright and can the artists stop big brands misappropriating it in this way?

The case started when Williams’ lawyer issued a cease-and-desist letter asking H&M to remove an advertising campaign for its New Routinesportswear line which used imagery and videos that incorporated one of his artworks. The campaign featured a model on a handball court posing in front of the Revok artwork. Williams maintained this was a case of copyright infringement, unfair competition and negligence – and that the association with the H&M brand was causing him reputational damage.

Fashion’s got previous

It is not the first time Revok has sued a big fashion brand. In 2014, along with graffiti artists Reyes and Steel, he took Italian fashion company Roberto Cavalli to court for copying an artwork created in San Francisco. The dispute was later settled out of court.

In this latest suit, H&M reacted by filing its own claim against Williams, stating that as his graffiti was created illegally without authorisation, they could exploit it. The company requested a court order to allow H&M to use the art in its campaign without having to pay the artist any royalty.

In other words, the Swedish fashion brand argued that illegal graffiti is vandalism and criminal trespass – so anyone should be able to appropriate it, for whatever purpose. It also claimed to have used a production agency to shoot the video, which was reassured by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation (NYCDP) that the artwork was not authorised and amounted to defacing of public property.

In the US, artistic works are eligible for copyright if they are original and can be fixed in a tangible medium, such as the side of a building. There is no doubt Revok’s mural in this case met these requirements.

Whether art produced illegally warrants protection is still a grey area of the law – not just in the US but also in the UK and other countries. I believe this case offers a good opportunity to shed light on this issue – and if the dispute is not settled, the judge should unequivocally clarify that unsanctioned original art is protected by a valid and enforceable copyright.

The defence employed by H&M is popular among defendants accused of appropriating and profiting from street artworks that have been created illegally. It has been raised, for example, by the fashion brand Moschino in a copyright infringement case brought by the graffiti artist Rime. He claimed that various elements of his Detroit mural Vandal Eyes had been copied on to a Moschino dress worn by pop star Katy Perry in 2015.

Copyrights and wrongs

H&M invoked the so-called “unclean hands doctrine”, a defence in which the defendant claims that the plaintiff should not obtain a legal remedy and profit when it has acted unethically, illegally or in bad faith.

I’m not a fan of this doctrine, especially when it is applied to unsanctioned art. What makes it unsuitable to govern cases of misappropriation of street art is the lack of connection between the illegal act committed by the artist and the merit of these disputes, namely the exploitation of the work by another party for commercial purposes. In other words, the illegal behaviour of the artist does not have a negative impact on the corporation which has misappropriated the artwork.

The way (legal or illegal) art is created should not affect the issue of copyright. If I steal a pen then use it to draw a wonderful piece of art, why should I be denied the right to enforce my copyright and allow someone else to copy and make money out of my work? It is simply unfair to allow others to copy and exploit it for their own commercial gain just because it is illegal.

Denying copyright to illegal graffiti would have the effect of making the misappropriating of it legal, but not its very creation. Feelings of resentment on the part of the street-art community, who perceived H&M’s move as an assault on artists’ rights, are entirely understandable.

It could also be argued that making copyright and enforcement rights available to street artists for illegally created works would be useless. Many would deem it risky to start a legal action as this would mean revealing their identity and exposing themselves to serious legal consequences, including jail. This is what Williams could face if, as H&M claims, it is found he had no authorisation to paint that mural.

It would be much less risky if a copyright suit was brought against those who exploit an artwork long after it had been created – like other offences, graffiti has a statute of limitations. In these circumstances, artists or even their heirs can be determined to sue big companies who are blatantly trying to free-ride on other people’s creativity.

After all, creativity should never be illegal. But ripping it off should be.